In June 1971, the North Carolina Medical Journal dedicated almost an entire issue to perinatal mortality in our state. Two years prior, with the help of the Maternal Health Committee of the State Medical Society (then the publisher of the journal), the North Carolina Obstetrical and Gynecological Society, and the State Health Department, the journal began keeping track of perinatal mortality rates for each county and individual cities with populations of at least 10,000.

The journal editors had planned to devote the June 1971 issue to a summary of the first year of the program, whose goal was to provide unbiased statistics about perinatal mortality to local physicians. But they quickly realized they needed more context to properly understand the data. So, they went back seven years, and what they found was shocking.

“The differences between low rates and high rates and the changes in some others were often of such magnitude and persistence as to suggest also that many physicians could not have been aware of the relative standing of their communities over this period of time,” wrote Dr. Herbert E. Bill.

The goal of Bill’s lengthy article appears to be to convince local physicians throughout the state of two things:

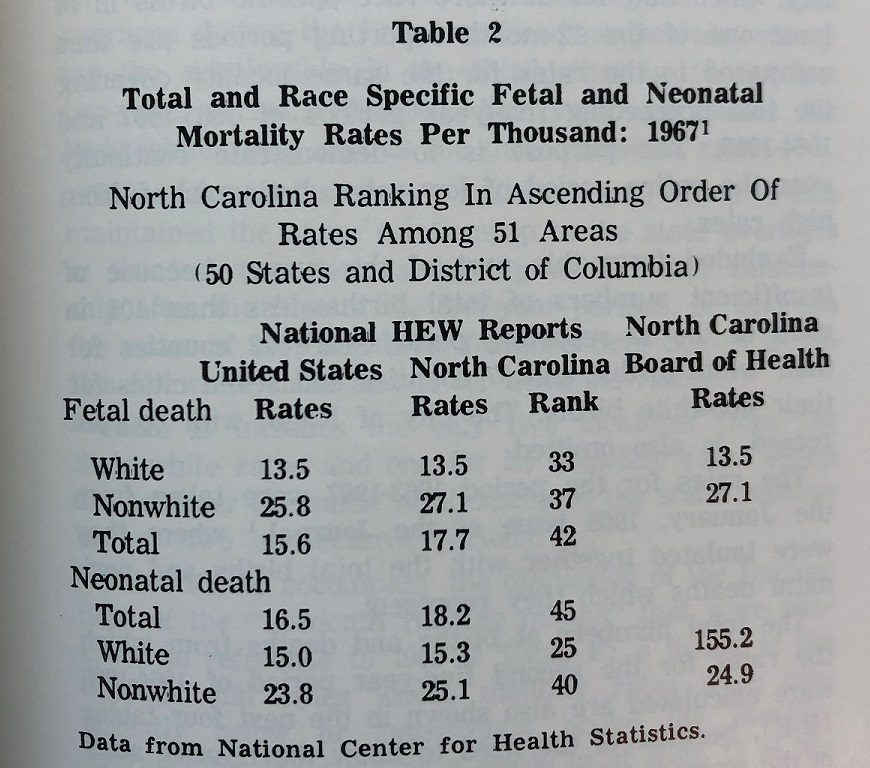

From our vantage point 50 years later, the article also provides some important perspective. North Carolina’s infant mortality rate (deaths within the first year of life) has improved significantly over the past 50 years, from 18.2 neonatal deaths (those occurring under 29 days of life, when most infant deaths occur) per 1,000 in 1967, to 4.6 deaths in the first 28 days of life per 1,000 live births in 2019. This was the lowest rate in more than 30 years, but racial inequities have increased: the White/nonwhite disparity ratio in 1967 was 1.6; today, the Black/White ratio is 2.4.

While these comparisons are not exact because the way we track this data has changed, they do illustrate the stubborn problem of combating infant mortality across all North Carolina communities. Part of the challenge is accurately identifying both proximate causes and the underlying drivers of infant mortality.

“If one were to put his finger on one problem that was common to any group of localities,” Bill wrote, “it would be . . . particularly or persistently high perinatal losses in their nonwhite populations although their white losses might be remarkably low.”

While North Carolina doctors documented racial disparities in perinatal mortality in 1971, the framework of upstream thinking was not as commonplace as it is today.

“[U]nless some common denominator escaped notice, the only suggestive association with consistently low and consistently high rates or, for that matter, with the more markedly changing rates seemed, by exclusion of other generally influential factors, to be some peculiarity or combination of peculiarities of the local situation,” wrote Bill. At the same time, he noted, “…there is nothing inescapably fixed or preordained about the level of perinatal mortality in a given community. The rates can apparently be altered, and gain regardless of race.”

In other words, people’s immediate environments – their socioeconomic status, the physical characteristics of their neighborhood, their access to food, or the availability of health care, or a combination of factors – seemed to be impacting their chances of experiencing perinatal mortality, but change was possible. Today, we would call this a focus on the non-medical drivers of health, with the “common denominator” sought by Bill the persistence of a major driver of infant mortality: structural racism. The effects of structural racism (the way public policies and institutional practices perpetuate inequities) are known to impact access to healthy opportunities and health care and result in poor health outcomes, including infant mortality. That’s why, 50 years on from Bill’s accounting of infant mortality in our state, the Healthy North Carolina 2030 initiative encourages policy makers and clinicians to take steps toward dismantling structural racism.

At the conclusion of his article, Bill expressed a hope that clinicians across the state would set aside their “suspicion of statistics” and get intimately involved with efforts to lower perinatal mortality rates at the local level. More recent data and anecdotal evidence from myriad public health initiatives in the years since have shown that many doctors took up this call, but there is much more work to be done.

As part of Healthy North Carolina 2030, the state’s public health community has a goal of shrinking infant deaths to 6.0 per 1,000 live births, and lowering the Black/White disparity ratio to 1.5. The work required to reach those goals is already being implemented in part by the Essentials for Childhood project, Governor Roy Cooper’s Early Childhood Action Plan, Prevent Child Abuse North Carolina’s Connections Matter campaign, MAHEC’s community-based doula program SistasCaring4Sistas, initiatives like UNC’s program to train more Black doulas in the state, the North Carolina Early Childhood Foundation’s Family Forward initiative, MomsRising’s paid leave advocacy, NC Child’s research and education efforts, and legislative efforts to extend pregnancy Medicaid coverage to up to one year after delivery. The NCIOM, in addition to participating in the aforementioned efforts, also continues to convene stakeholders and policy makers in this work through the Task Force on Maternal Health and the Perinatal System of Care Task Force.

Click here to read the 1971 article, Seven Years of North Carolina Perinatal Mortality Rates.

For more on this topic from the NCMJ:

Maternal and Infant Mortality in North Carolina (2021)

A Retrospective Look at North Carolina’s Efforts to Reduce Infant Mortality (2016)

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Infant Mortality in North Carolina, 2008-2009 (2016)

Addressing Infant Mortality Disparity Rates in a Small Rural County (2012)

Infant Mortality: 1963 to Present Medical Developments and Legislative Changes (2004)

North Carolina’s Infant Mortality Problems Persist: Time for a Paradigm Shift (2004)

Improving Pre-pregnancy Health Is Key to Reducing Infant Mortality (2004)