Healthy North Carolina 2030 (HNC 2030) identifies key public health indicators for our state. The State Health Improvement Plan has engaged statewide leaders in ongoing efforts to improve the health of North Carolinians through policies, programs, and systems related to these health indicators. One key indicator, access to healthy food, faces significant funding changes under the passage of House Resolution 1 (HR1), the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The North Carolina Institute Of Medicine (NCIOM) is exploring possible impacts of federal legislation on food access in North Carolina and what these impacts mean in the latter half of this decade.

Federal legislation enacted in July 2025—HR 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act —introduces sweeping changes to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Over the next decade, the program faces a $187 billion cut, with some projections estimating that upwards of 22 million US families might lose some or all of their SNAP, also known as food stamp benefits [1, 2].

Funding cuts and cost burden shifts in HR1 will impact individual beneficiaries in North Carolina as well as state and county budgets. This article highlights how changes to the Thrifty Food Plan, work requirement updates, cost burden shifts, education funding, and non-citizen eligibility revisions might impact North Carolinians in the coming years.

The Thrifty Food Plan (TFP) is one of four food plans measured by the USDA to estimate different price points for a healthy diet. The TFP is the lowest of the four food plans, and it is used to calculate SNAP benefit maximum allotments each October [3].

Beginning on October 1, 2025, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) will be required to account for changes in the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, a key measure of inflation, when updating the Thrifty Food Plan [4]. By 2028, the Thrifty Food Plan also must be cost neutral [5].

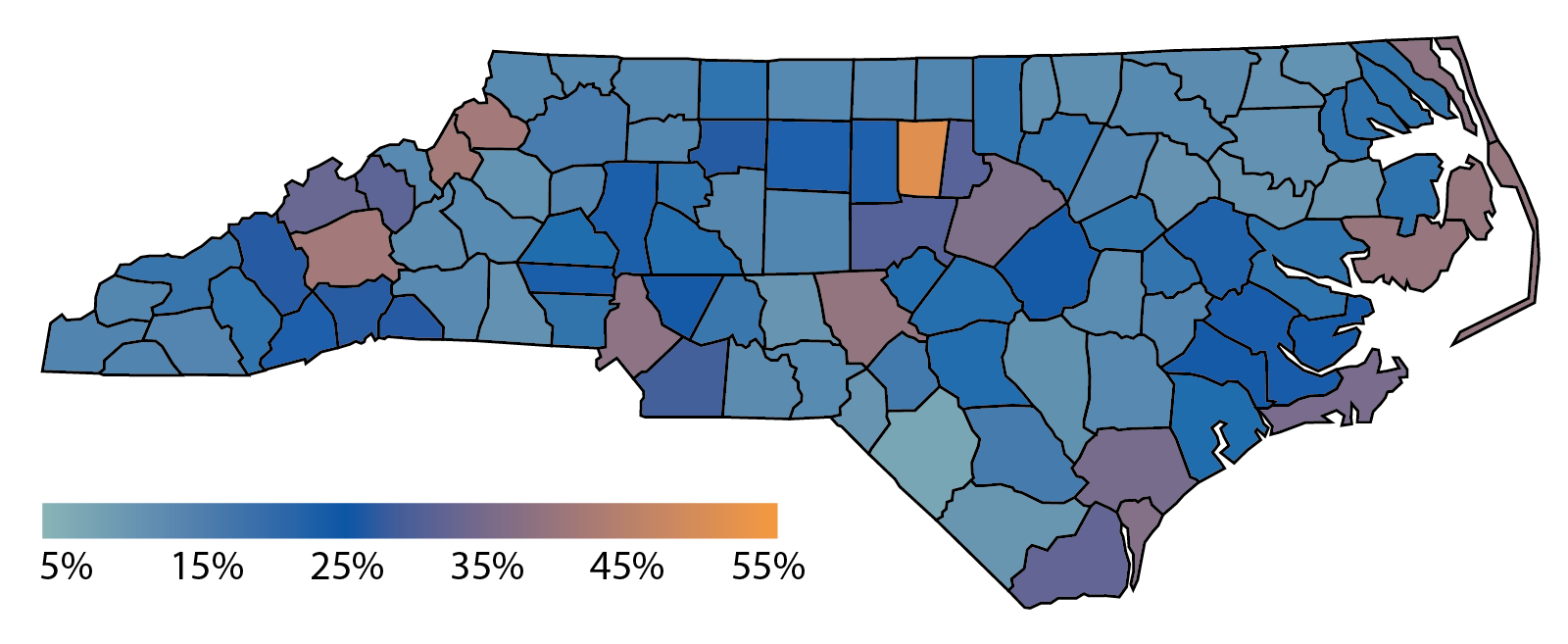

Historically, SNAP benefits have struggled to keep up with rising food costs. In 2024, SNAP benefits did not cover the cost of a moderately priced meal in 99% of US counties [2]. In 2024, North Carolina SNAP benefits did not cover that cost in all 100 counties. Orange County was the most expensive and Robeson was the most affordable county to purchase and prepare a moderately priced meal [2].

Figure 1: SNAP Benefits Gap by County, 2024

Note: This map shows the percent difference between the maximum SNAP benefit per meal and the average cost of a meal prepared at home.

Source: www.urban.org/data-tools/does-snap-cover-cost-meal-your-county

According to the Urban Institute, the new provisions in HR1 will continue to limit how effective SNAP benefits are in helping low-income beneficiaries access healthy food [2]. Both the cost neutrality and inflation factors will further restrict how high benefits can be raised annually.

Prior to HR1, most able-bodied SNAP participants between 16 and 59 already had to meet a general work requirement, including: “registering for work, participating in SNAP Employment and Training (E&T) or workfare if assigned by your state SNAP agency, taking a suitable job if offered, and not voluntarily quitting a job or reducing your work hours below 30 a week without a good reason” [6]. Able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) typically also have to meet additional work criteria, including working 80 hours per month, participating in a work program for at least 80 hours per month, or a combination of the two [6].

Beneficiaries that fall into either the general or ABAWD categories could meet certain exceptions from work requirements. Several exceptions changed under HR1, including [4]:

All SNAP work requirement changes were effective immediately upon enacting HR1.

In North Carolina, 1 in 8 people receive SNAP benefits, according to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services () [7]. Of the 1.4 million beneficiaries [7]:

Beginning in fiscal year 2028, a new matching fund requirement established in HR1 will go into effect. Matching fund requirements will be based on payment error rates, with states that have error rates above 6% paying from 5% to 15% of SNAP benefit costs [8].

SNAP payment error rates are tracked by the USDA and measure each state’s accuracy in determining eligibility and benefit levels. The measure includes both overpayments and underpayments [9].

In 2024, ony nine states and territories had error rates below 6%. Since 2022 (no data is available for 2020 and 2021), North Carolina’s error rates have been near or above 10%. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the state’s error rates were consistently low, below the new 6% threshold [9].

In addition to potential matching payments based on error rates, all states will be required to pay for 75% of the administrative costs for their SNAP programs beginning in fiscal year 2027, up from 50% prior to HR1’s passage [4].

Based on current error rates, NCDHHS estimates a $420 million annual cost increase under the new matching fund requirement. Due to the administrative cost shift, NCDHHS also anticipates a $65 million cost increase at the state level and $14 million increase at the county level [10].

HR1 eliminated all funding for the SNAP Nutrition and Obesity Prevention Grant Program (SNAP-Ed). SNAP-Ed funding is used to provide healthy eating and active lifestyle education and is administered through state governments and local grantee organizations. North Carolina’s SNAP-Ed program, which receives about $11 million per year, has been managed by the North Carolina Division of Child and Family Well-Being, with nine implementing agencies across the state [11, 12].

HR1 also amended SNAP eligibility to be for US citizens, certain lawful permanent residents, Cuban and Haitian entrants, and residents from the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau [13]. Undocumented immigrants have never been eligible for SNAP benefits, leaving legal refugees as the primary group removed from benefits eligibility under this new definition [14].

Food assistance in North Carolina is entering a period of significant change. HR1 funding changes will reshape how many families access support, and it is likely that a significant number of North Carolinians will lose SNAP benefits, either due to ineligibility or an increased application and certification burden.

The full impact is still unknown and will significantly rely on the state government’s ability to increase its own appropriations, underscoring the need for policy discussions to identify state and local opportunities to provide support.

_______________________________________________

Written by

Brady Blackburn

Communications Director, NCIOM

Managing Editor, NCMJ

_______________________________________________