Written by Erin Bennett

In March, state leaders around the country undertook efforts to limit non-essential business and encourage citizens to remain in their homes to curb the spread of COVID-19. As the risk of the virus became progressively more apparent, state governments themselves transitioned into remote working arrangements and put in place new temporary protocols to provide government services online, through email, or over the phone. However, certain aspects of the judicial system have ground to a halt in the midst of the pandemic.

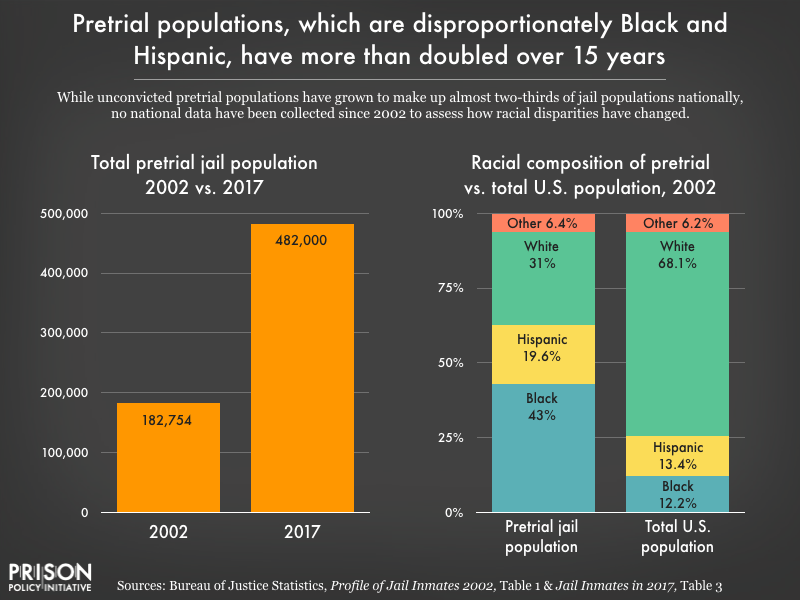

In North Carolina (like many states), jury trials at the district and superior courts have been suspended since May, and are not expected to resume before the end of September.[1] The effect of this is that many people will remain in jail pending their trial. The bail system in the United States is designed to ensure that those charged with crimes appear for their trials, yet it often functions as a financial gatekeeper—releasing those who can afford to pay bail and confining those who cannot. Further, the system also disproportionately affects communities of color and other marginalized groups. Although efforts have been undertaken across the country to limit the applicability of bail to lower level offenses, in the United States, approximately half a million people are currently confined to local jails pending trial or an alternative resolution of their case.[2]

Even without factoring COVID-19 into the picture, pretrial detainment can have devastating effects on the health and well-being of both detainees and their families. Persons awaiting trial from a jail cell often lose their job and any health benefits they may have through that job. This loss is particularly acute for those who may have already had difficulty finding a job that would accept applications from persons with criminal records. In the face of lost income, pretrial detainees and their families may be unable to make rent or mortgage payments and risk losing their housing. Detainees may also suffer a blow to their social support networks, as they may be unable to afford the cost of phone calls, their families may be unable to travel to visit, and some may risk losing parental rights if a co-parent seeks court intervention while they are detained. All of these effects compound the existing stress of detainment in jails—facilities that are often overcrowded, underfunded, understaffed, and plagued by poor environmental conditions such as dampness, mold growth, and ventilation concerns. Additionally, studies[3] have shown that pretrial detainment practices have a disproportionate negative impact on Black and Hispanic persons. This may be attributable to over-policing of communities of color, pretrial risk assessment tools that bias those affected by structural racism and are more likely to lead to higher bail amounts for persons of color, and the fact that persons who have been systemically marginalized often cannot afford bail.

The communicability and serious health impacts of COVID-19 have added a new layer to existing health concerns surround pretrial detainment. Since those incarcerated in jail cannot observe “social distancing” or other strategies designed to limit the spread of the virus since they are at the mercy of shared facilities, they are at elevated risk of contracting the virus. In fact, nationwide, incarcerated persons are 2.5 times more likely to be infected with COVID-19 than the general population. Some jails have sought to curb spread of the virus by eliminating visits from family and legal representatives and largely keeping detainees confined to their cells, effectively placing them in solitary confinement—a practice that has known detrimental mental health effects. Regardless of the administrative approach to controlling the virus, many jails are overcrowded, underfunded, and lack the medical staff necessary to serve the incarcerated population, particularly those with preexisting conditions who may experience added physical hardship from interruptions in their existing treatment protocols.

Further, non-emergency health services in jails often are accompanied by co-pays—fees that detainees who have lost their jobs and face unemployment when they are released, and whose families cannot afford to support them, may not be able to afford. In North Carolina, many jails have waiver systems for medical fees, but the systems are not standardized across the state, and some treat the waiver as a deferral and maintain an accounting of waived fees for later settlement.

Over the last few months, fearing rapid spread of the virus through incarcerated populations, some county leaders in North Carolina (along with other localities nationwide) have worked to decrease jail populations by releasing those held for minor offenses if the individual does not pose any public safety concerns. However, for those who are not eligible for these emergency protocols, detainment may seem near interminable as they await trial. While the Sixth Amendment technically guarantees defendants a right to a speedy trial,[1] measures of what constitutes an acceptable delay are not standardized, and it is unclear how that right will play a role moving forward if courts continue to be impacted by the virus and jury trials remain suspended.

[1] On July 16, 2020, Chief Justice Cherie Beasley issued Emergency Directive 22 which instructs senior resident superior court judges to develop a “Jury Trial Resumption Plan” aimed at developing safe procedures for holding jury trials in the coming months.

[2] Studies have shown that those who cannot afford bail are more likely to take a plea deal regardless of the strength of their defense, as it may seem like the fastest way to get out of jail, particularly for those charged with low-level offenses.

[3] It is worth noting that the most recent nationwide study assessing the demographic breakdown of pretrial detainees was conducted in 2002. This is in spite of the fact that the pretrial detainee population nationwide has continued to grow rapidly.

[4] It is of note that when executive and judicial orders delaying court proceedings were challenged under the Sixth Amendment by a pretrial detainee whose trial had been continued, the court determined that the orders were appropriate in the context of the public health crisis and thus were not violative of the detainee’s rights.