By Kaitlin Ugolik Phillips

Earlier this month, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a special report warning that the world must undertake “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented” action to keep global temperatures from increasing 1.5°C. That limit is half a degree lower than the target set by the Paris climate agreement in 2016. The report explains that many researchers believe a 2°C increase would be too dangerous and examines what it would take to keep the global temperature at the lower level. Their conclusion: carbon emissions would have to fall by 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050 to prevent catastrophic effects such as sea level rise; stronger heat waves, floods, and droughts; and the decimation of coral reefs, among others.

What does this mean for the health of North Carolinians?

Coming in between Hurricane Florence and the remnants of Hurricane Michael, the IPCC report was illustrated in a particularly visceral way for many in our state. As the managing editor of the North Carolina Medical Journal, I wanted to help bring this issue home by highlighting some of the scientific reports and analysis we have published on health impacts related to climate change.

Most recently, the September/October 2018 issue of the journal focused on Environmental Health in North Carolina. Authors in this issue drew attention to some of the climate-related issues facing North Carolinians, from extreme heat to ambient air pollution to coal-powered electrical plants and coal ash impoundments. Gregory D. Kearney of East Carolina University evaluated the socio-vulnerability characteristics of population groups in Eastern, Piedmont, and Western North Carolina and found that the eastern part of the state had a disproportionately higher percent of population groups vulnerable to the threats of climate change.

What can be done?

Health care providers need to understand and communicate the challenges faced by rural and otherwise vulnerable population groups in this part of the state to policymakers, Kearney writes.

Health professionals can also play a major role in identifying those climate-change-related challenges. Lauren Thie of NC DHHS and Kimberly Thigpen Tart of the National Institute of Environmental Health Services wrote recently in the journal about the effects of extreme heat exposure and wildfires on vulnerable North Carolinians and highlighted some of the professional training programs that put our state’s health professionals in a good position to address these problems.

Past Success

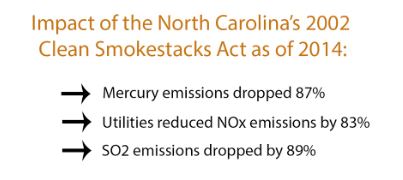

The impact of climate change can feel like an overwhelming problem, but North Carolina has made progress on climate-related health policy in the past. Thanks to the North Carolina Clean Smokestacks Act and related policies, the state saw better air quality that has been credited with reductions in respiratory, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular health.