Written by Emily Hooks

The recently released Healthy North Carolina 2030 goals reflect a broad range of factors that impact the health of North Carolinians and the state’s priorities for improving health over the next decade. Because North Carolina public school buildings are now closed for the remainder of the academic year, we’re highlighting barriers associated with improving third grade reading proficiency and the impact COVID-19 may have on that proficiency.

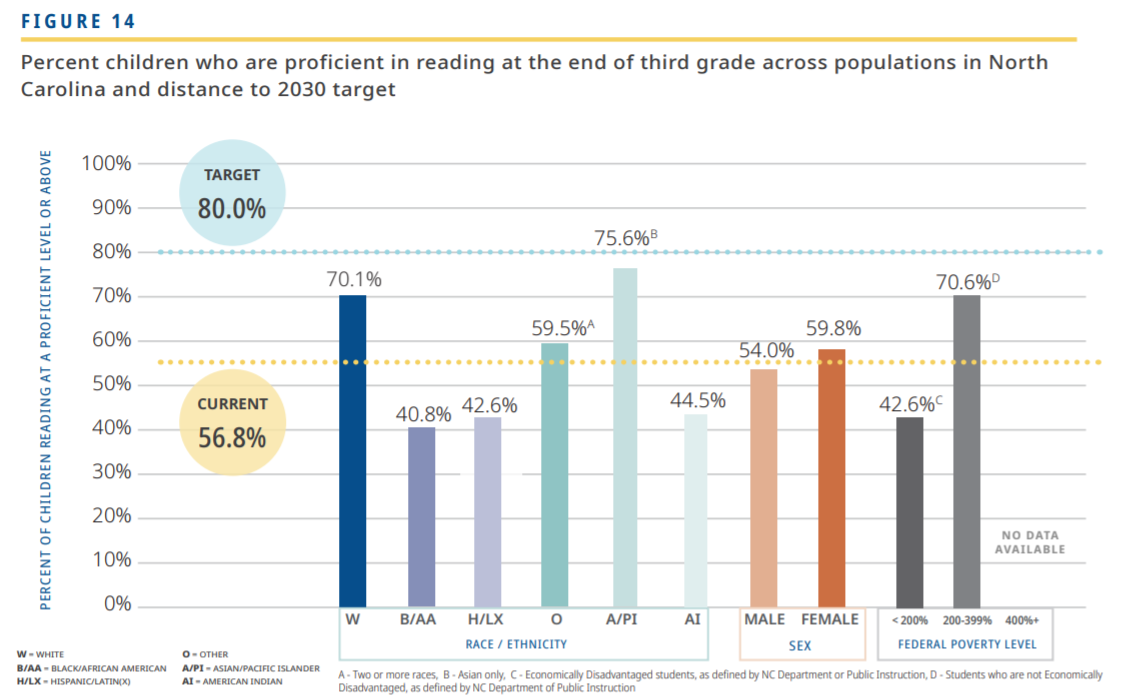

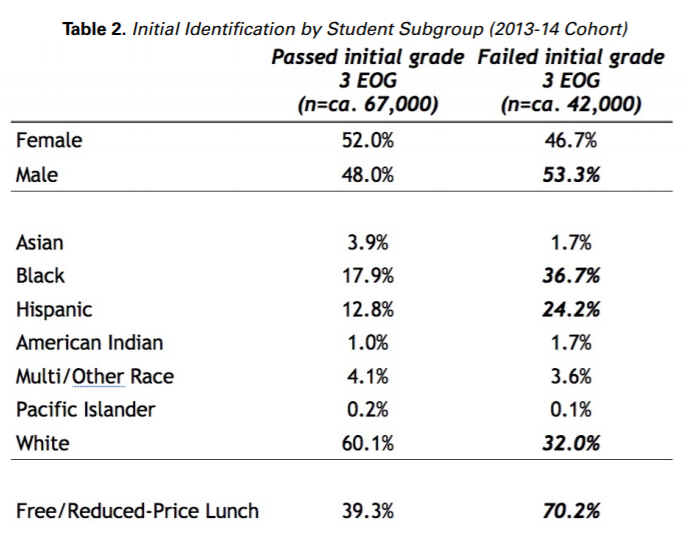

One of the most pivotal milestones for mastery is the third-grade reading end-of-grade test. Students who do not demonstrate proficiency (defined as level 3 or higher) often face compounding academic difficulties and are at increased risk for dropping out of school, as well as future adverse health outcomes. Past results of the North Carolina third-grade reading end-of-grade test illustrate a stark achievement gap between economically disadvantaged students and higher-income students and between white students and African American, Hispanic, and American Indian students (see figure). While the long-term impact of COVID-19 on this gap remains to be seen, existing data already show the disparate instruction students are currently receiving based on their access to broadband internet and devices.

Since March 16, schools across the state have provided remote instruction for students. Local education agencies (LEA), North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI), and the General Assembly are grappling with how to support students as they receive that remote instruction. For most students, this means using a computer or smart device and multiple learning management systems, apps, or websites. This instruction requires broadband internet, and at least 259,000 North Carolina households do not have access to adequate broadband in their homes. In a recent survey conducted by the Broadband Infrastructure Office and the Friday Institute, 67% of respondents cited cost as the primary reason they do not have broadband internet in their home. In addition, families who only have one computer, tablet, or smart phone will be at a distinct disadvantage if multiple children in a household are expected to receive instruction online for multiple hours a day, and/or if parents are using the device for work. In last week’s presentation to the House Select Committee on Education, the State Board of Education and NCDPI shared that they have identified 300,000 students without devices. This digital divide will almost certainly cause achievement gaps for low-income students to widen further, and it is certainly even more detrimental to students who are experiencing homelessness.

The state received a federal waiver to forego standardized testing, and it is likely that legislators will grant the State Board of Education’s request to suspend statewide testing requirements. Without standardized testing to measure student learning and teacher effectiveness, it remains unclear how the state will ensure students are proficient in grade level content, including the third-grade reading milestone. State officials do not have a precedent for school closures of this duration to guide decision-making.

Recent research shows that students in New Orleans needed two full school years to regain lost knowledge following school closures and displacement after Hurricane Katrina. Students of color and economically disadvantaged students experienced greater negative impacts on their learning after Katrina. Students of color and economically disadvantaged students in North Carolina have historically scored lower on third grade testing, indicating there was already a need for greater support for those students prior to COVID-19.

Following Hurricane Katrina, students in New Orleans also experienced persistent and ongoing trauma; emerging information about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and families—including heightened risk for child maltreatment, adverse economic impacts, and increased rates of domestic violence—indicate that many students in North Carolina will experience trauma that may negatively impact their educational success and long-term health and well-being.

After past prolonged school closures (due to natural disaster and/or public health emergencies), some countries and states have chosen to include reforms to improve equity within schools after reopening. As the state develops plans to adjust delivery and goals of instruction during and following the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers can look to initiatives such as NC Pathways to Grade-Level Reading, a NC Early Childhood Foundation initiative that addresses how the state and communities can improve third grade reading proficiency and improve equity. Applying lessons from equity-focused initiatives and past public health emergencies can help North Carolina improve educational quality, ensure greater equity, and support children’s health and well-being.

Read more in the A Path Toward Health series here:

Limited Access to Healthy Foods