Written by Erin Bennett

The recently released Healthy North Carolina 2030 health goals reflect the broad range of factors that impact the health of North Carolinians, and the state’s priorities for improving health over the next decade. Throughout the coming year, we will feature the chosen health goals in a series called “A Path Toward Health.” For the second edition in this series, we’re highlighting barriers associated with accessing healthy foods, many of which have been exacerbated by the ongoing COVID19 pandemic.

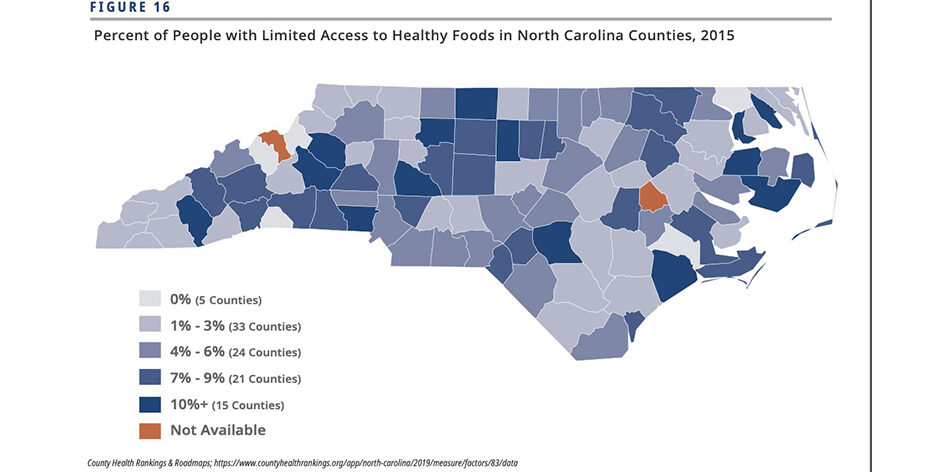

A healthy and nutritious diet is an integral part of physical and mental well-being and a protective factor for chronic conditions such as obesity and diabetes. Across the state, many North Carolinians live in food deserts [1] and routinely struggle to access healthy food to feed their families. Often in these areas, the most accessible places to shop for groceries are small convenience or corner stores, many of which may not have a wide variety of healthy options [2].

The difficulty that many North Carolinians face in accessing healthy foods is magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic and the efforts that have been undertaken to limit its spread. In addition to increased difficulty navigating transportation and business closures, many families who face financial barriers to affording healthy foods rely heavily upon child care centers or school lunch programs to make sure their children are getting nutritious meals. The closure of the public schools across the state has led to many children losing a primary source of healthy meals, putting them at risk for food insecurity and the lasting health impacts of poor nutrition. The pandemic may also impact older adults and immunocompromised persons who may not feel safe leaving their homes to go to food banks, grocery stores, or other places where they usually get food.

To help support food insecure children and adults during the pandemic, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NC DHHS) has temporarily increased Food and Nutrition Service benefits (formerly known as food stamps), extended benefit certification periods, and suspended work requirements. These changes are designed to afford families greater flexibility in using their benefits. In an effort to support the nutritional needs of schoolchildren, Governor Roy Cooper has allocated additional funds to help school systems maintain operations remotely and continue school nutrition programs. Finally, the state and No Kid Hungry NC have created a text message-based resource and a daily map resource, respectively, to help parents locate places where they can receive food assistance for their children.

Other organizations have also taken steps to fight the added burdens on food insecure individuals and families across North Carolina. Food banks and food delivery services for vulnerable groups like Meals on Wheels have continued to operate, despite increased demands and decreased volunteer support, and have worked to ensure that food distribution processes are in accordance with public health directives. Grocery stores and other food retailers have modified standard practices to create special morning shopping hours for older adults and vulnerable persons.

Moving forward, fighting the impacts that the COVID-19 pandemic is having on access to healthy foods will likely require coordination of public and private efforts. In a letter released on April 1, 2020, NC Child and its partners called on the General Assembly to act to remove barriers to qualifying for public nutrition assistance and also appropriate state funds for private organizations such as food banks and farmers markets. These initiatives would support the work already done in both the public and private sector to connect those facing food insecurity with reliable sources of healthy foods.

Read more in the A Path Toward Health series here.

[1] The US Department of Agriculture defines a food desert as a low-income metropolitan area where at least a third of residents live more than a mile from a grocery store, or a low-income rural area where at least a third of residents live more than ten miles from a grocery store. Low-income areas are defined as those with “a poverty rate of 20 percent or greater, or a median family income at or below 80 percent of the statewide or metropolitan area median family income.”

[2] In 2016, North Carolina funded the Healthy Food Small Retailer Program, designed to provide support to small food retailers in food deserts to stock healthier food options. Although the program has been successful in helping 11 stores across the state build infrastructure to carry a greater range of fresh, nutrient-dense products, logistics barriers remain to extending the program’s reach.