by Guest Authors Jennifer Runkle (North Carolina State University) and Maggie Sugg (Appalachian State University)

Hurricane Helene, one of the most catastrophic storms to impact the US mainland since Hurricane Katrina in 2005, brought unparalleled devastation to Western North Carolina (WNC)—a region unaccustomed to extreme weather events. Essential services were paralyzed as regional water systems collapsed, leaving residents without reliable or clean access to water for several weeks. Helene’s impact has only magnified existing challenges in maternal health, exacerbating longstanding disparities in a field already under strain in this rural region, a maternal care desert marked by significant OB/Gyn clinic closures and maternity wards that limit access to essential maternal and prenatal services.

The storm claimed at least 102 lives at the time of writing and inflicted severe damage to infrastructure, washing out roads and isolating entire communities (NCDHHS 2024). However, the full impacts of these tropical storms are not well accounted for, and recent evidence reveals that their effects persist long after the initial devastation, leading to excess mortality rates for up to 15 years post-storm, particularly among vulnerable groups such as infants, low-income residents, and communities of color (Young and Hsiang 2024).

These long-term health consequences underscore the need for a more comprehensive approach to disaster recovery that addresses immediate relief and sustained support for at-risk populations. Here, we advocate for a focus on pregnant women and children, as these groups are particularly susceptible to both immediate and long-term health effects of environmental disruptions, including increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and mental health challenges (Harville et al., 2021, Lafarga et al., 2022, Currie et al., 2013, Herbst et al., 2024).

Before Helene, maternal health services in WNC were already insufficient due to a severe shortage of health care providers specializing in obstetrics and gynecology, compounded by the closure of hospitals that offered obstetric care (e.g., six labor and delivery units have closed since 2015). The rural and mountainous landscape of the region, coupled with high poverty rates and limited transportation, posed significant barriers to accessing care, often forcing pregnant women to undertake long travel times to receive necessary services. According to data from the March of Dimes—a maternal health advocacy organization that tracks health data from various federal sources—before the hurricane, only half of local facilities offered prenatal and delivery care for the region’s approximately 153,000 women aged 18-44 (Bigrance et al., 2022).

The consequences of such limited access are well-documented: women in rural areas are more likely to forgo prenatal care, which can lead to severe health complications, including severe maternal morbid conditions like preeclampsia and hemorrhaging (Kozhimannil et al., 2016; Sheffield et al., 2024, Singh 2021). Hurricane Helene’s destruction has further isolated rural communities, leaving expectant mothers at heightened risk as they struggle to access critical prenatal and postpartum care.

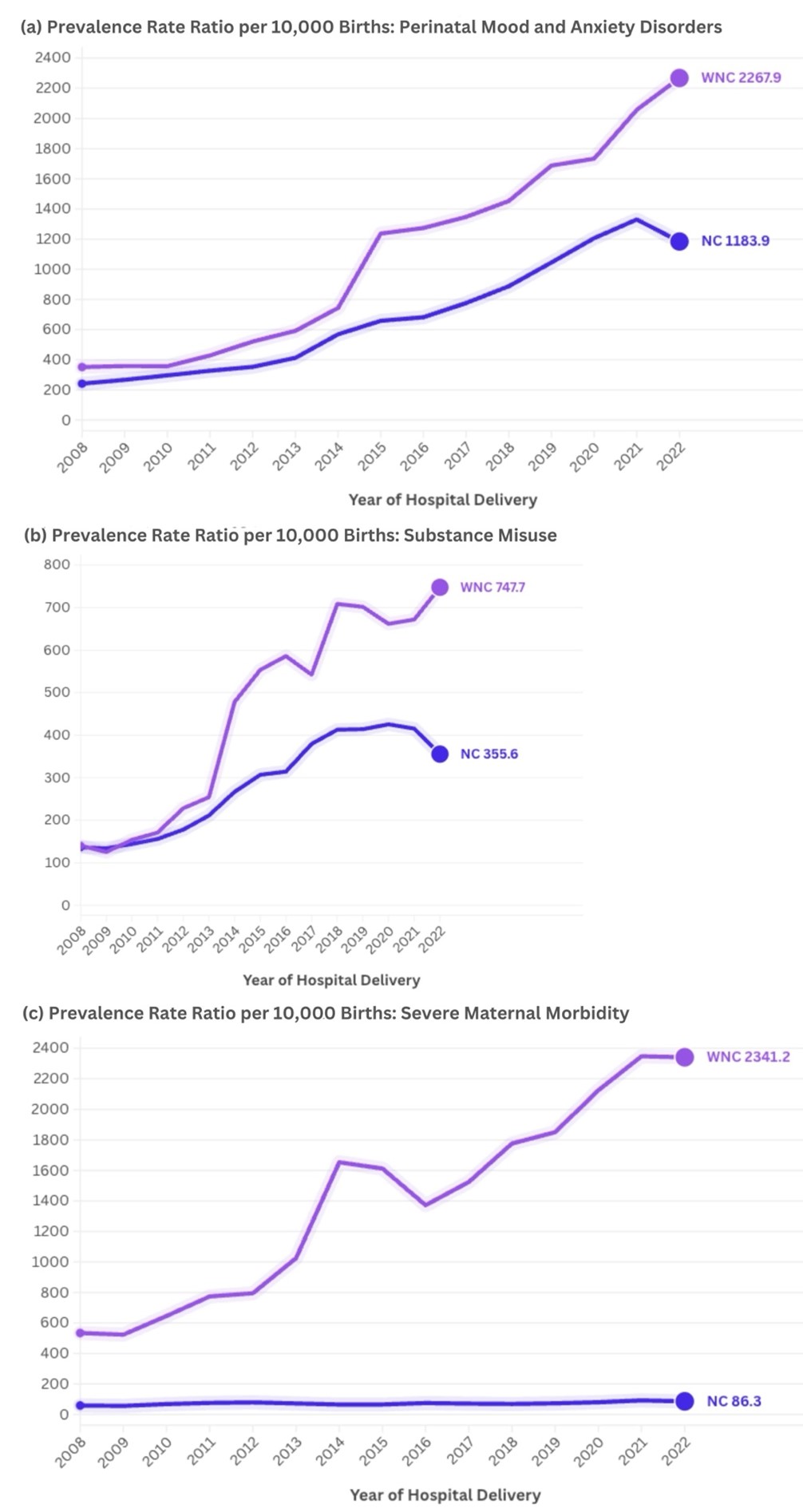

These disruptions significantly elevate the chances of maternal and infant complications, posing profound implications for families across WNC and deepening an already dire health care crisis in the region. Notably, even before the storm, maternal mental health, severe maternal morbidity, and substance use rates in WNC far exceeded state averages (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Annual prevalence rate rations per 10,000 hospital deliveries for a) perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, b) substance misuse, and c) severe maternal morbidity in Western North Carolina (WNC) and North Carolina (NC), 2008-2022

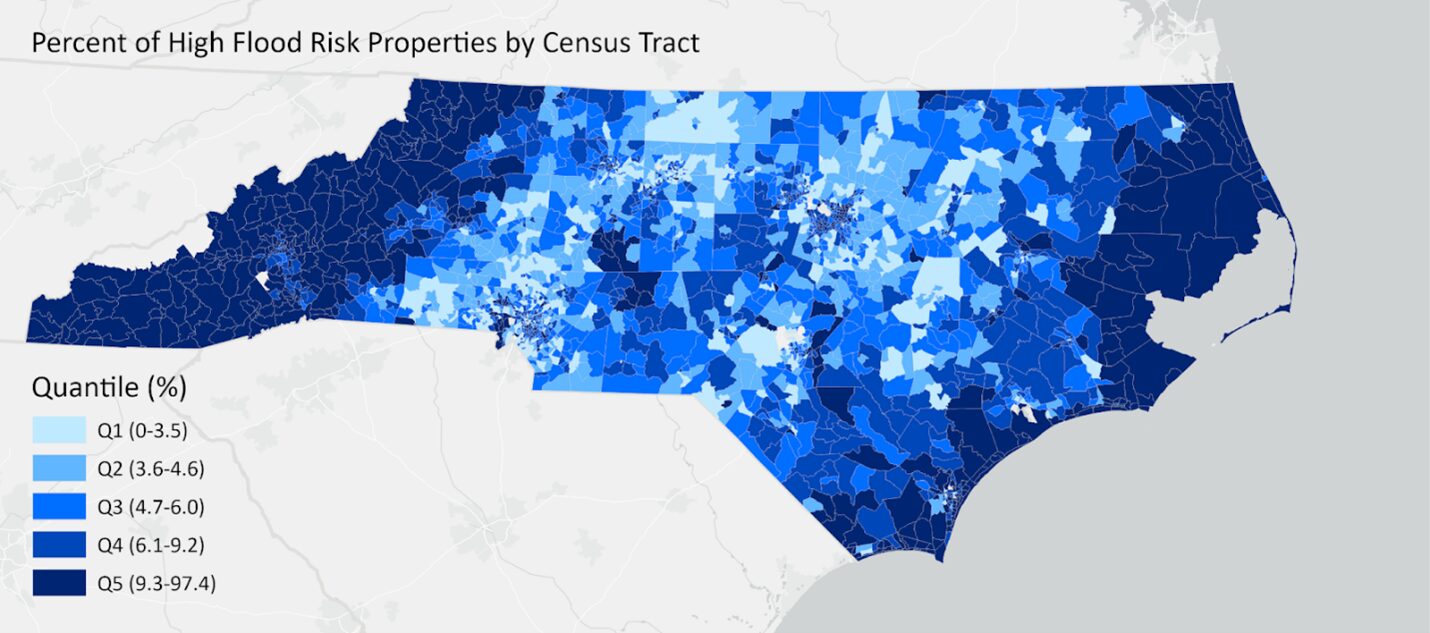

Climate disasters like Helene amplify these underlying maternal health disparities. Despite the region’s high number of properties vulnerable to flooding, most homes lack flood insurance through programs like the National Flood Insurance Program (Figure 2), adding to the economic strain on affected families.

Figure 2: Map of flood risk for North Carolina by census tract based on First Street Foundation’s Flood Factor data

The impacts of Helene underscore the urgent need to address WNC’s pronounced health disparities, particularly in maternal mental health and prenatal care. This ongoing disaster highlights the urgent need for targeted policies that address the specific vulnerabilities of pregnant women and their developing children, as pregnancy represents a critical window in environmental stressors, adaptation, and resilience (Davis and Narayan, 2020). For instance, the prenatal period is particularly susceptible to climate extremes, as it involves rapid psychological and physiological changes in both mother and fetus, amplifying the impacts of climate-induced stressors (Barker 1998).

This stage also provides an essential opportunity for interventions, as pregnant women often have heightened access to health care (e.g., through expanded Medicaid) and may be especially motivated to enhance health behaviors in preparation for childbirth (Davis and Narayan 2020, Davis et al. 2020, Narayan et al. 2016). In addition, existing research underscores that environmental stressors during pregnancy can have lasting effects on mother and child health (Barker 1998, Currie and Rossin-Slater 2013).

Despite the critical needs of pregnant women and infants in disaster contexts, policy frameworks often lack emphasis on resilience-promoting measures for these at-risk populations. This oversight results in significant gaps in mental health support, access to safe housing, and continuity of maternal healthcare services.

Community health workers (CHWs), doulas, and midwives have expertise that can be invaluable before a disaster strikes. Investing in these roles provides a high return in community health and resilience. They can play an essential role before, during, and after disasters like Helene by preventing costly health complications through early intervention, education, and regular monitoring. As trusted community members, these allied health workers can educate on potential health risks and connect families to critical services. They serve as first responders, delivering on-the-ground primary health care, assessing needs, and offering emotional support and mental health first aid (Nicholls et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2023; Monteblanco et al., 2019). These professionals act as navigators for displaced or isolated families due to damage to roads, clinics, or hospitals, ensuring that at-risk populations—those most affected by disasters and least likely to have access to health care—receive the care they need.

Implementing new care models and policy measures will strengthen health care resilience, ensuring pregnant populations and children receive the support needed to mitigate immediate and long-term health impacts from climate disasters. By prioritizing maternal health in disaster recovery and reinforcing health care infrastructure, we can reduce health disparities, support at-risk populations, and create a more resilient and equitable response to future climate events.

_______________________________________

Guest posts are the author's views and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NCIOM.

References

Barker DJ. In utero programming of chronic disease. Clin Sci Lond Engl 1979. 1998 Aug;95(2):115–28.

Brigance C, Lucas R, Jones E, et al. Nowhere to go: maternity care deserts across the US (report no 3). March of Dimes. 2022. https://www.marchofdimes.org/maternity-care-deserts-report

Currie, J., & Rossin-Slater, M. (2013). Weathering the storm: Hurricanes and birth outcomes. Journal of Health Economics, 32(3), 487-503.

Davis EP, Hankin BL, Glynn LM, Head K, Kim DJ, Sandman CA. Prenatal Maternal Stress, Child Cortical Thickness, and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms. Child Dev. 2020 Mar;91(2):e432–50.

Davis EP, Narayan AJ. Pregnancy as a period of risk, adaptation, and resilience for mothers and infants. Dev Psychopathol. 2020 Dec;32(5):1625–39.

Harville, E. W., Beitsch, L., Uejio, C. K., Sherchan, S., & Lichtveld, M. Y. (2021). Assessing the effects of disasters and their aftermath on pregnancy and infant outcomes: A conceptual model. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 62, 102415.

Herbst, K., Malmin, N. P., Paul, S., Williamson, T., Sugg, M. M., Schreck, C. J., & Runkle, J. D. (2024). Examining recurrent hurricane exposure and psychiatric morbidity in Medicaid-insured pregnant populations. PLOS Mental Health, 1(1), e0000040.

Lafarga Previdi, I., Welton, M., Díaz Rivera, J., Watkins, D. J., Díaz, Z., Torres, H. R., ... & Vélez Vega, C. M. (2022). The impact of natural disasters on maternal health: Hurricanes Irma and María in Puerto Rico. Children, 9(7), 940.

Narayan AJ, Bucio GO, Rivera LM, Lieberman A. Making Sense of the Past Creates Space for the Baby: Perinatal Child-Parent Psychotherapy for Pregnant Women with Childhood Trauma. Zero Three. 2016;36:22–8.

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Hurricane Helene storm-related fatalities. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved November 10, 2024, from https://www.ncdhhs.gov/assistance/hurricane-helene-recovery-resources/hurricane-helene-storm-related-fatalities

Young, R., & Hsiang, S. (2024). Mortality caused by tropical cyclones in the United States. Nature, 1-8.